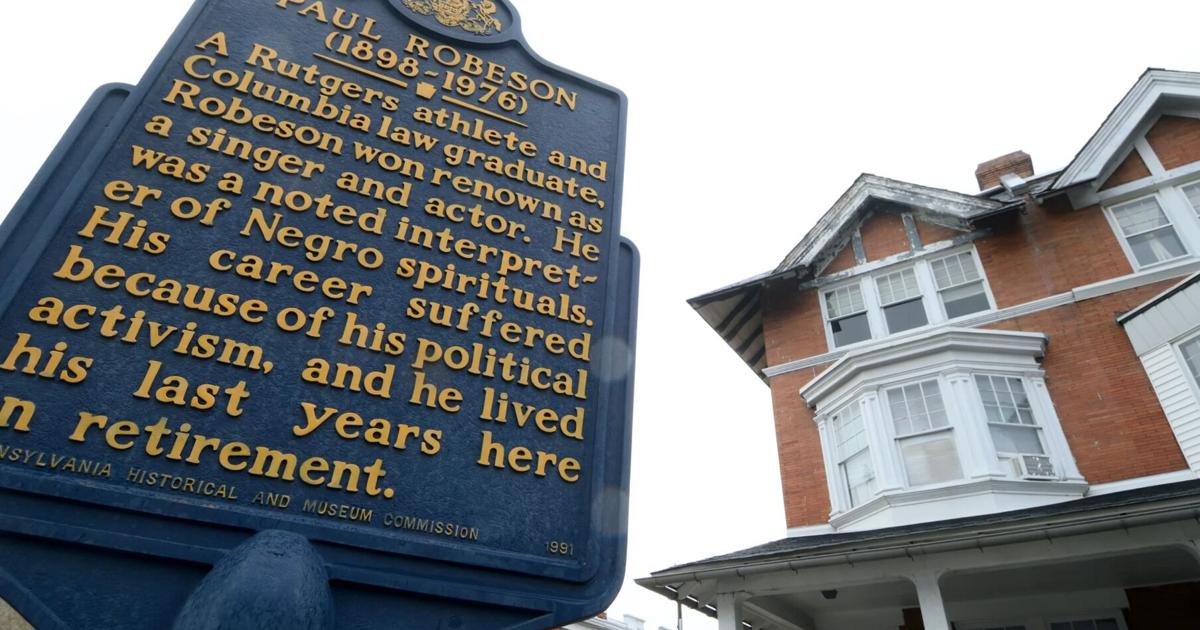

At the end of his life, famed singer, actor, activist, and athlete Paul Robeson came to live in West Philadelphia in 1966 with his sister Marian R. Forsythe. They lived in a three-story home at 4951 Walnut St. After moving in with his sister and her husband, Dr. James Forsythe, Robeson could often be seen waving at neighbors from the large front porch. He also welcomed many of his celebrity friends to the house, including actors Harry Belafonte, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee.

Almost 50 years after his death, the Paul Robeson House and Museum is scheduled to reopen to the public on October 10 with a grand reopening celebration. This follows eight months of major renovations. During the reopening, the building will be officially renamed and now includes expanded office and archive space, a renovated kitchen and event hall with a capacity of up to 150 people, and the Paul Robeson House Artist-in-Residence suite.

Azsherae Gary, interim executive director of the Paul Robeson House, said the latest renovations to the annex were made possible by funding from the Mellon Foundation. “We started renovations last August and finished one phase in April,” she said. “So, we’re now celebrating this accomplishment and welcoming folks back into the space, hoping they will come and keep Paul Robeson’s name alive.”

The house is filled with memories that visitors will find visible throughout the space. Starting at the front door, guests are greeted by a unique, life-sized stained-glass image of Robeson that looks almost as if he is still there to welcome them inside the quaint, warm space. Upstairs, inside the annex, Robeson’s original bedframe is on display, adorned with an artistic bedspread and antiques representing the era in which he lived.

There is also an old-fashioned radio that may have once played his songs, and an antiquated television set with all of its knobs and an antenna, typical of the World War II era. Visitors will find a variety of books, including one written by Robeson’s granddaughter, as well as his old albums such as “Ballad for Americans,” “Paul Robeson at Carnegie Hall,” and “Encore, Robeson.” A screen stands ready to show snippets from his life, songs, and movies.

Among the museum’s other treasures are photographs, small carvings, a piano, and a music book. Some pieces were donated by The Charles Blockson Museum at Temple University. The Paul Robeson House also sponsors an in-house artist-in-residence, Shanina Dionna, who specializes in healing arts and mixed media. Dionna helps run various summer programs, some of which are supported by an Independent Public Media Grant, the University of Pennsylvania, and the William Penn Foundation.

The museum also collaborates with the West Philadelphia-based Paul Robeson High School and assists with a yearlong training program for ninth and tenth-grade students.

As an activist and lawyer, Robeson was described in many ways, according to Gary. “Clearly, he grew up at a time when racism was very blatant in this country,” she said. “I would say maybe the first 20 to 30 years of his life focused on art, music, and his work ethic. As he got older, he began traveling globally and saw what Black people and others were experiencing in other countries. He started to realize that something was wrong in America. So, he began to speak out about that. He was ostracized for it. He tried to say, ‘Hey everyone, we’re human here. We should be treated equally and respectfully.’”

In the 1920s, Robeson appeared in a controversial play about interracial marriage, which was illegal in the U.S. at the time, titled *All God’s Chillun Got Wings*. He was also the first African American to play the starring role in the Shakespearean play-inspired movie *Othello* opposite actress Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona in 1930.

Robeson broke further ground by starring as the first African American lead in the film *King Solomon’s Mines* in 1937. He also appeared in the 1932 movie *Showboat*, where he sang his famous low rendition of “Ol’ Man River.”

His ties to the Philadelphia and New Jersey areas include graduating from Rutgers University, where he was the third Black student to be accepted and the first Black player on the college’s football team. Robeson sometimes experienced discrimination both from his own teammates and from opposing teams, and was once benched when students refused to play football with a Black player.

Hannah Wallace, the museum manager, emphasized the importance of places like the Paul Robeson House and Museum, especially at a time in contemporary American history when some African American historical icons are being hidden or overlooked. “I’d say that is important for public memory and for the confidence of a community,” she said. “Just to have our heroes remembered — and being able to have them represented on the street. It is important to see them inside an institution, but also out on the street, through murals and through statues. It’s important for the people and for the environment, because when you have these sites, people respect the space more and also respect the history.”

The museum will be open from Wednesday through Saturday, from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. There will be a $12 admission fee for adults and $6 for children ages 12 and under, starting with the October 10 grand reopening.

“I’m hoping that we get visitors internationally — folks come here from overseas,” Gary said. “We get a lot of students, scholars, researchers, and anyone who cares to learn about history in West Philadelphia. I want them to come in,” she added. “I want them to learn. I want them to have a good time. I want them to enjoy themselves.”

https://www.phillytrib.com/news/local_news/paul-robeson-house-in-west-philadelphia-set-to-reopen-with-mission-to-educate-inspire/article_c8e0ac43-8935-4a82-a9e0-35a1e617958a.html